January 1, 2014 / Jacques Vos

I. Introduction

In times when techniques are rapidly advancing, the need to reduce administrative burdens – especially in times of financial crises – is becoming a priority. Public authorities try to find a ways to cut costs. It is important that lawyers help to recover the real estate market by improving confidence and cut costs where and when possible. Therefore, the transfer of ownership and mortgaging an immovable should be as efficiently as possible, both in a Member State and cross-border.

Lawyers, in particular notaries and registrars, have the opportunity to contribute to the recovery in the (European single) market by being creative and innovative. European legislation focuses on the realization of a European judicial area. This legislation is hardly used. Registrars, united in the European Land Registry Association, tried to promote the use of these European Directives and Regulations by starting a cross-border electronic conveyancing project.

This paper first gives a small comparison and description of the characteristics of an average lawyer, followed by an introduction to a Cross border e-conveyancing project, called Crobeco[1]. The project members gained much practical experience during the project. Next to the practical approach based on ‘the three respects of Crobeco’, the legal meanings and regulations are outlined. In addition, the issues that the project partners met and had to solve, are part of this paper.

Respect for existing techniques is one part of the all-embracing respect for existing circumstances. In the Netherlands we found a way to process property deeds fully electronically without loosing responsibilities on either side. This method of processing deeds is part of the Cadastre’s Chain integration program[2]. The main goal of this program is to lower administrative burden, enhance quality of data input into the Cadastre registration system and fasten the process of conveyancing. The acceptance of this program partly depends on the practical interpretation and procedure in order to stimulate progress. Perhaps this approach is helpful because of the characteristics of lawyers. I conclude that participation in new projects, such as the European Crobeco project and the national chain integration program, is a real opportunity for lawyers who want to anticipate to the rapid changes in the legal field.

II. Characteristics of lawyers

In order to describe the characteristics of a lawyer in modern times, we could try to compare him or her to two other academics: a (cardiac) surgeon and a physicist.

Let us first take a look at the cardiac surgeon[3] who has a patient with a bad heart who needs surgery. The circumstances in which the surgeon has to perform surgery will vary each time depending on location, available state of the art equipment and other factors such as culture. But the functioning of a human heart is (or should be) the same wherever the surgery takes place. Surgeons took an oath and try to do the best they can to save the life of a person and / or to cure the disease. This makes the surgeon hungry for new technological solutions to improve operating techniques and subsequently improve his rate of success.

If we now look at the lawyer, we see some similarities with the surgeon. He or she also took an oath to do the best that (s)he can to realise the best outcome. Furthermore the lawyer also informs and warns the client of risks that may arise during the whole process. But there are also some differences. In comparison to cardiac surgeons, most lawyers do not embrace new technologies; certainly the traditional lawyers do not. New technologies make lawyers cautious. And that is completely understandable from a certain point of view. It is the task of a lawyer to prevent any risk and complete transactions unscathed. It is also for that reason that people trust lawyers, protecting them against legal risks and uncertainties. Most of the time lawyers think in terms of problems and afterwards they try to find a solution to those problems. The traditional lawyer hardly ever thinks in terms of possibilities.

It is believed that everyday practices in today’s society are developing fast. Techniques are changing and developing at a tremendous pace, and sometimes legislation can not keep up. Because legislation is drafted technology proof most of the time, generic terms that need to be crystallized are introduced. That is why I believe Case Law becomes more and more important in many legal systems and lawyers have to become inventive solution-thinkers. Inventivity might cause a risk, especially since it is probably not part of a lawyer’s nature. But in the face of challenging trends in the (legal) marketplace and new technologies for the delivery of legal services, lawyers have to move on. Although lawyers will not become obsolete in the age of the Internet, the rising potential of newly developed software and the Internet might put them out of business in some areas. Lawyers who derive their status from the information asymmetry between them and their clients may be asked less for their legal services.[4][5]. They have to think more creatively, imaginatively and entrepreneurially about the way in which they can and should contribute to today’s rapidly changing economic and societal times[6]. Lawyers, especially the traditional ones, should try to think more like a surgeon and explore. Try new techniques[7]. But of course, you don’t let the patient pass away. The responsibility to decide to adopt new technologies will lie with the Registrar since the Registrar’s role is to maintain legal certainty. In the end, technology is only a means to an end and not an end in itself. Legal certainty is the priority in the application of new technology, as IT must be subordinated to the legal demands. The moment at which the reverse is the case is the moment at which the Registrar has to stand up and draw a line to protect legal certainty.

As we compare lawyers to physicists, we meet another characteristic of lawyers. For a physicist it is established that the gravity he or she perceives in Amsterdam is the same physical phenomenon, and is subject to the same laws as the gravity that his/her colleague perceives in Madrid. The effects of gravity change depending on the location, which might surprise unsuspecting lawyers traveling around the world[8]. But it will not surprise the physicist, since even this effect is subject to law (the physical law of gravity). In other words, the physicist studies a wide range of physical phenomena (in different branches of physics), describes the movement of the matter concerned through time and space and couched it in a physical law.

Comparing the lawyer to the physicist, the average lawyer looks at legal conception as determined by the law which these figures belong to. As a maximum result (s)he will study the similarities and differences between these figures and the law they belong to, see where possible problems might occur, but will not easily explore new possibilities.

Lawyers in other words try to stick to their own legal system and legal concepts, despite the movement towards harmonization and globalization.

Within Europe, the European Commission uses the Four Freedoms[9] as a framework when taking the different legal systems of each Member State and converging them into one European legal system. The four freedoms help to remind policy makers that citizen’s legal certainty must remain priority over economic benefits when making laws and legislation. There are some challenges to realise this merging of systems and concepts, even in cases of more or less equivalent results[10]. Although many national legislations are already based on European Directives1[11] and Regulations[12], mutual recognition is not taken for granted. There are still many distinctions between and within legal systems and the techniques that are used.

III. Different legal systems, different characteristics

It is (almost) impossible to describe the various existing legal systems and to differentiate their characteristics. Therefore, the following is not an attempt to give an all-embracing enumeration. That is why I give a very brief overview of (some of) the legal systems and especially focus on the characteristic distinctions, regarding the transfer of ownership and mortgaging immovable’s.

First, there is the difference between common law with its ancient legal traditions (on procedural law and equity) and the more recent civil law systems on the continent.

Second, there is the distinction between title systems and deed systems and there are the differences in pragmatism and dogmatism within these legal systems, with their legal traditions on substantive law) and the different (legal) cultures. In the event of a title system, the legal status of an immovable is always as is recorded in the Cadastre registration. A third party, consulting this register may rely on the accuracy of the registration. In the event of a deeds system the legal status may differ from the information, recorded in the Cadastre registration. There is a possibility of so-called hidden charges[13].

With regard to mutual recognition and the harmonization and globalization, there is the distinction between Member States with a more Monistic and Member States with a more or less Dualistic view, although this distinction became of less importance because of Van Gend en Loos [14]and Costa/Enel[12].

And between all of these differences there is the stance of the average lawyer as explained in the previous chapter. Finally, there are different roles for different key players such as Notaries and Solicitors but also different responsibilities between Notaries and Registrars.

These different systems, cultures, roles and responsibilities can sometimes cause ambiguities and sensibilities, especially when foreign legal practitioners and new technologies become involved. In that playing field the Registrars tried to pave the road towards cross border electronic conveyancing.

IV. CROBECO

Keeping in mind the specific characteristics of lawyers (Chapter 2) and the distinction between and within the different legal systems (Chapter 3), the Crobeco project fits well into this frame, because of its step by step approach and the respect for existing circumstances.

IV.1. The reason Crobeco existed

More and more people have chosen (by the virtue of the ‘freedom of movement of capital’) to invest in second homes in another EU country, maybe as a holiday home, a retirement prospect or for holiday purposes. Many have found themselves entangled in impossible legal nightmares. There have been deposits lost or disappeared, legal fees and overdue taxes, buildings not being built at all or built in breach of local planning legislation[17][18]. Lots of problems occur possibly because of unclear communication between the seller and buyer, both speaking their own language or due to different national legislation. That is where Crobeco, the abbreviation of Cross Border Electronic Conveyancing, is trying to help.

The European Land Registry Association (ELRA) has conducted research to identify an alternative process for foreign electronic purchases of real estate in countries, where registration of foreign deeds is admitted. The Crobeco project[19] helps to simplify the practical implementation of one of the fundamental principles of the European Union as set out in the Treaty of Union[20] at Article 3.21 An important side effect is the realization of a simpler and confidence inspiring procedure of the acquisition of foreign immovables. It is achieved by creating an electronic process, fully settled in the country of the foreign buyer.

The right to property as laid down in article 17 of the charter of fundamental rights of the European Union22 implies that Europeans should not be deprived of their possessions without a fair compensation and only by public interest reasons, as long as set out in the law. This includes a right to choose the law that is applicable to contractual and non contractual obligations concerning their property rights. The right to make such a law choice is laid down in Regulations Rome I and Rome II[23] and the Regulation on matters of succession and on the creation of a European Certificate of Succession[24]. Although application of these regulations is prioritized in the specific programme civil justice[25], apart from the CROBECO pilot, in practice the law choice is not made in conveyancing contracts. The reason for that is probably a lack of a suitable conveyancing process. Possibly, the reason for this is the lack of a suitable process for cross-border conveyancing. This process should enhance cross border transactions through the common space of freedom, security and justice and promote free circulation of documents, with the objective of the single market of real estate. CROBECO aims to develop such a conveyancing process. It improves the protection for a foreign buyer in case of simple cross border transactions as it aims to set out a European framework of rules and principles for a process that, for both contractual and non-contractual obligations, is based on the law choice of the parties and the use of digital means. The framework is referred to as Cross-border Conveyancing Reference Framework (hereafter CCRF)[26] and could improve confidence of foreign buyers in reliable cross border conveyancing because it gives foreign buyers of real estate the option to opt for trustworthy home country legal protection.

This alternative process for purchasing foreign real estate is based on a bilingual deed, executed by a Notary public in the foreign buyer’s home country. The deed is written in two languages: the buyer’s native language and the official language of the country in which the plot is located. The contract stipulates that all contractual and non contractual obligations are governed by the law of the foreign buyer’s home country. This increases confidence in the adequacy of legal protection and makes prospective buyers less reluctant to buy foreign properties. Use of the process will be voluntary. The results could help the recovery of the real estate market in Southern European countries.

IV.2 Practical pilots and conferences

The different ELRA-members that have been involved in the project did not want to create a project where the theoretical approach was predominant. There was no intention to first draft the whole process and afterwards a practical case had to be found, bearing in mind the Crobeco principles as explained in Chapter 4.4. It had to be a project where the Registrars and Conveyancers were learning on the job, where practical and theoretical problems are solved during the process of cross border electronic conveyancing and where Registrars gave effect to the already existing European legislation[27] .This legislation and the cross-border use of qualified electronic signatures were implemented into daily practice.

First of all, a case where a foreign buyer was willing to use a newly thought mechanism of conveyancing, based on existing legislation, by using his or her own Conveyancer had to be found. Of course it had to be a case in a European Union Member State where foreign (authentic[28] ) deeds are accepted by Registrars. Since a Spanish court gave a ruling that it is possible to register a foreign deed in the Land Register, Spain became the first ́receiving country ́ in the Crobeco pilot[29]. Since, amongst others[30] , a lot of Dutch people are buying houses in Spain and a Dutch Notary[31] was willing to participate in the project, the ‘sending country’ turned out to be the Netherlands.

That is why at the first conference in 2010 a Dutch buyer bought property in Spain using the Crobeco process. In Brussels a Contract of Sale in both the Dutch and the Spanish language was sent live to the Spanish Registrador, using a qualified electronic signature[32] . After that, the process was put into practice by sending several contracts of Sale and was evaluated at the second conference in Tallinn (Estonia). The comments made by several organisations[33] and persons were taken into account and solutions for obstacles encountered were added in a final report that was presented during the Closing Conference in May 2012 in Brussels. This is where the first cross border mortgage deed, again in the Dutch and Spanish language, was sent real time to the Spanish Land Register by the Dutch Notary, using his qualified electronic signature[34].

IV.3. Description of a case

To explain the practical use of the CROBECO project, I now describe a case where a buyer from Member State A buys a house in Member State B.

Buying in the traditional situation

Let us meet Mr. Smit, a Dutchman[35]. Mr Smit is buying a second home in Spain and is very happy as he finally succeeded in buying a house with a beautiful view that he was hungry for. Looking out from his garden near the beach he is sure he will enjoy the Mediterranean Sea for many years. But then Mr. Smit finds out that the building is situated in a public domain near the coast, where building a house is very restricted according to the Ley de Costas (Spanish Coastal law). If he had known that his beautiful house was located on this public domain and therefore the house perhaps has to be (partly) demolished, he would not have concluded the contract. The Spanish Notary did his research, but it was not clear to Mr. Smit it was not clear whether the Notary did research on the existence of public restrictions or not. The Notary drafted the deed at his office and a few days later both seller and buyer signed the deed. Mr. Smit was not told about any public restrictions by the seller, or perhaps he was, but Mr. Smit did not understand the foreign language. Poor Mr. Smit does not speak Spanish quit well. According to the Spanish system, Mr. Smit becomes owner by signing of the deed and paying the purchase price. Registering the escritura (Contract of Sale) in the Spanish Land Register allowed him to invoke the transfer before third parties. Later on, being the new owner, Mr. Smit received a warning that he has to pay the overdue contributions to the common hold association and overdue taxes that the seller forgot to pay. Mr. Smit is heavily disappointed. To make matters worse, he receives a message that the soil of the property is polluted and needs sanitation. Had he known that an alternative procedure existed, he would have asked his local Crobeco notary.

Buying with the help of CROBECO

Again we meet Mr. Smit. This time Mr. Smit has found a Dutch Notary who is participating in the Crobeco project. Mr. Smit asks this Notary to draft a Contract of Sale containing the protective clauses, both seller and buyer agreed on. These clauses are available as textual examples in the Crobeco Repository. The first clause is a clause on indemnifications. By using this clause, Mr Smith does not have to be afraid of overdue payments, the absence of a building-permit and the protection against public encumbrances that are not mentioned in or attached to the contract of sale.

The second clause concerns the choice of law. Mr. Smit and his (Dutch) opposing party agreed to have a possible dispute resoluted according to Dutch law. This choice of law is possible because of Regulation Rome I[36]. As far as the transfer and acquisition of ownership and the validity and effects of recording the deed at the Registro de la Propiedad concerned, the Spanish law is applicable, in accordance with the Lex rei sitae.

A third clause added in the Contract of Sale concerns the jurisdiction in case of disputes about these contractual obligations. Dutch Mr. Smit and his seller agreed on the fact that a Dutch Court of Law will have jurisdiction in case of a dispute that has arisen or may arise in connection with a particular legal relationship. As a consequence, a Dutch Court gets the authority to judge on consequences and compensation in case of violating the agreements, listed in the contract[37].

The last additional clause is based on Regulation Rome II and creates liability for the seller to Mr. Smit for non-contractual obligations, related to the contract. This specific additional clause makes Dutch law applicable for non contractual obligations and grants authority to a Dutch court by means of the choice of law. That is why Dutch Contract Law will be applicable.

According to article 15 of book 7 of the Dutch Civil Code[38] the failure to report on overdue taxes and contributions is a violation and because of the choice of Dutch law as the applicable law, Mr. Smit could get a Dutch court order in which the seller was condemned to compensate the extra payments Mr. Smit has to pay to the common hold association.

Then there was the concealing of information about the location of the plot and the pollution, the seller did not tell Mr. Smit. If Mr. Smit would have known about this situation, he would not have concluded the contract. He considers the concealing of information concerning the public domain as a violation of the duty of the seller to disclose burdens as described in consideration 30 of the Regulation Rome II[39], also know as culpa in contrahendo.

The methodology for compensation depends on the law of the country where the plot is located (lex rei sitae). Because Spain has a title system, the transfer of ownership is inviolable. Because of the choice for Dutch jurisdictions on non contractual obligations, Mr. Smit gets a new court order in which the seller is condemned to buy the property for a fixed purchase price. Pursuant to article 6 paragraph 1 of the Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5th of April 1993 on unfair terms in consumer contracts, a judge who concludes the nullity of an unfair clause in the contract is not entitled to convert the unfair clause into a clause that is permitted[40].In other words, Member States shall lay down that unfair terms used in a contract concluded with a consumer by a seller or supplier, as provided for under their national law, will not be binding on the consumer and that the contract shall continue to bind the parties upon those terms if it is capable of continuing in existence without the unfair terms.

If the buyer had not been Mr. Smit from Holland but Mr. Smith from England or Mr. Schmidt from Germany the results should be the same, if Dutch law is declared applicable in the Contract of Sale. If a rule as Dutch article 15 of book 7 is missing, Smith or Schmidt could have such a clause added as an extra condition in the contract[41].

IV.4. The Crobeco principles

As already mentioned before, Crobeco uses the step by step approach. This means that the Registrars and Conveyancers are learning on the job and the project as well as the different pilots was given shape in small steps.

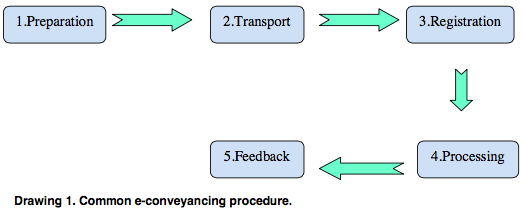

The process of electronic conveyancing exists of 5 different steps. In some Member States a view of these steps are merged or combined, but even then the process can be outlined as is represented in the drawing below.

Crobeco is not meant to change existing legislation, techniques and responsibilities. It is meant to foster trans-border cooperation in the interests of European citizens. For the European Commission the focus on the European citizen, who wants to use the four freedoms, is vital to understanding the functioning of the Internal Market. The four freedoms are essential for a successful Internal Market and therefore, also for Crobeco.

Crobeco therefore, respects the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality, while at the same time it is promoting further cooperation among Member States.

That is why Crobeco`s main principle was ‘no change to existing circumstances’, disaggregated into ́the three respects ́.

These three main topics are:

- respect for existing responsibilities;

- respect for existing legislation; and

- respect for existing techniques.

IV.4.1. Respect I: respect for existing responsibilities

The responsibilities between the Registrar and the Conveyancer (sometimes) differ per Member State. This is closely related to local habits, the use and culture, as well as it is closely related to the legal system (deeds or title systems) of a specific country. As is explained in chapter 3 there are all kinds of legal systems, with their own legal regimes, responsibilities and cultures. Sometimes in one country there is even more than just one legal system in use[42].

Crobeco did not want to make any changes within these legal systems. As the CCRF[43]focuses on bilateral agreements with respect for existing legislation, the CCRF should be applicable in Member States with different legal systems, although the existence of different systems will lead to different demands. In each of these Member States the law of the country where the plot is located (Lex Rei Sitae) determines the acquisition of property and applies to all questions related to real rights.

That means that the different responsibilities between Registrar and Conveyancer within an existing legal system should stay intact. Otherwise Crobeco would create certain unclarities between the legal professionals or even a legal system would have to be changed to meet the requirements set by the project. In some other Member States it seems Notaries and Registrars can not find an easy way to join forces and cooperate[44]. In countries where there is few cooperation the intention to make any changes in respect to the different responsibilities could raise questions. One of these questions might be whether the added value of one certain group of legal professionals is still justifiable or not[45]. In the Netherlands the relationship between Notaries and Registrars has been a very cooperative one for decades, although sometimes this cooperation is questioned[46].

Crobeco tries to improve the cross border electronic conveyancing, using the existing legal systems. The national electronic cross border conveyancing process should not be disrupted because of the cross border aspect. The CROBECO process complies with the common space of freedom, security and justice as defined in the Stockholm Programme[47] and in the Commission Action Plan[48]. In order to get free circulation of documents, as is (also) one of the aims of the Eufides project, but with suppression of formalities as legalization and apostil. Crobeco is based on the use of electronic documents with qualified signature and is therefore, in accordance with European and National legislation.

In the case of the conducted pilots this means the Spanish Registrar, because of the Spanish title system, scrutinizes the deed and asks the Dutch Notary for additional prove[49]. In the Dutch deeds system this documentary evidence is not to be submitted to and scrutinized by the Dutch Registrar because of the limited examination by the Dutch Registrar as prescribed by law[50]. As one of the questions asked during the second conference in Tallinn was about the risk of fraud, Crobeco turns out to be just as safe or perhaps even more safe than the traditional conveyancing process, because the additional prove and supporting documents (annexes) are scrutinized twice: at first by the Dutch Notary and afterwards by the Spanish Registrar.

IV.4.2. Respect II: respect for existing legislation

By describing the case of Dutch Mr. Smit in chapter 4.3. this second pillar of leaving the existing circumstances unaltered is already spoken about. There will be no proposal for alteration of national legislation. The existing legislation is the only tool to be used, next to the European existing legislation. Especially this last category is of great use. Crobeco is fully based on the legal principles and possibilities, using the European Regulations (Rome I, Rome II and Brussels I). By applying these Regulations foreign buyers can be protected by relying on their own, and thus familiar, legislation. There is no need to change any national law, although there are barriers to be removed: according to Dutch legislation, the Registrar is only allowed to accept deeds executed by a Dutch civil law Notary (article 31 of Book 3 of the Dutch Civil Code). Furthermore there are formal requirements, such as mandatory use of the Dutch language (article 41 of the Dutch Cadastre Act). The question is to what extent this legislation will maintain, if the refusal of the foreign deed by the Dutch Registrar is disputed. There is a tension between the refusal of the deed according to national law and the European four freedoms.

The European Court of Justice recently ruled that the notary has no direct public authorities, because parties agreed to the content of the deed themselves and the notary can not change the deed (easily) without the cooperation of the parties. Therefore, the European notaries do not have to have the nationality of the Member State they are working in. Perhaps the exception in article 2, paragraph 2, and sub 1 of the Services Directive is no longer justified.

Because Dutch registrars do not consider it to be the task of the registrars to examine Dutch law for compatibility with European legislation, deeds drafted by foreign notaries are refused. In my opinion it is questionable whether such a refusal shall be affirmed by the judge. It would not fit the Regulation on jurisdiction, applicable law, recognition and enforcement of decisions and acceptance and enforcement of authentic instruments in matters of succession and on the creation of a European Certificate of Succession, as it will come into force on the 17th of august 2015. In article 39 and 69 it is stipulated that establishing other conditions and/or restrictions on the Certificate is not permitted. The Certificate will consist of standard forms with fixed positions and fixed translations. Such is not the case with foreign deeds. That is why according to the Dutch registrars`opinion, the principle of publicity provides a valid justification for demanding a literal translation in Dutch. This translation will be recorded; the original deed will be kept by the registrar for evidential questions.

4.4.3. Respect III: respect for existing techniques

Within the different European Member States, different technical solutions are in use, each of them fitting in the (national) circumstances. For one, there is the electronic lodging. With this electronic system a digital duplicate is sent to the Registrar. The original paper deed is sent afterwards. The second method contains the sending of electronic documents without sending a paper deed afterwards. This system is called electronic registration. On receipt of the documents by electronic submission, the Registrar must still process the dealing of the registration. The most advanced system is the electronic conveyancing system[51], where transactions are done without paper throughout (almost) every stage of the process and the Land Register is updated automatically.

Crobeco does not want to compel the use of a specific technique, although the project wants to reuse already existing techniques that are used or developed by the European Large Scale Pilot projects (LSP’s)[52].

In the case of the CROBECO-pilots, the Spanish Registrar verified in advance whether the Certification Authority of the Dutch Notary is allowed to issue qualified certificates and, therefore, provides an opportunity for verification[53]. The Registrar assists the sender by verifying whether the dispatch has arrived unchanged. This was done on the basis of a hash value control. Before transmission the application of the sender calculated a unique control number for the file to be sent (the so-called hash value). This number was converted to an electronic signature and sent to the Registrar, who deciphered the electronic signature and compared the hash value which has become visible in this way with the hash value of the received document. If these were the same, the document has clearly not been changed during transfer. A set exchange protocol had to be observed for electronic delivery. Using the above mentioned techniques, the project contributes to the free circulation of documents[54].

IV.5 For conclusion

The Crobeco project has finished in May 2012, after several successful pilots were completed throughout the two years the project existed.

The need for sufficient support for foreign Conveyancers is adopted by adding a description of a helpdesk, a glossary, e-conveyancing guidelines and a repository. Quite recently a Grant was awarded to Crobeco II, a continuation of Crobeco, where a helpdesk will be established for foreign Conveyancers, where Conveyancers not only ask questions about the legal system and the specific national legislation but also about the local restrictions and taxes. The glossary will help the foreign Conveyancer to understand the meaning of the wordings, as the guidelines should explain the main features of each legal system. The repository with basic clauses for the transmission and mortgaging of property is meant as practical advice, but not mandatory for the exact wording of the contract. It could nevertheless be of great use, since the Conveyancer is sure these clauses will be accepted by the Registrar. The CCRF has been adopted in 2012 but is never going to be finished or closed. It will be a tool which matures in time and will be revisited constantly as techniques and circumstances change quickly. The responsibility for the decision to adopt these new technologies and already existing possibilities will lie with the lawyer, since the lawyer’s role is to maintain legal certainty. For the Land Register this lawyer is called a Registrar.

This paper is an adaptation of a paper written for and presented at the Cinder congress of 17, 18 and 19 September 2012 in Amsterdam. The title of the original document reads: «Electronic & Cross-Border Conveyancing techniques, cutting edge practice law» and was written together with Wim Louwman. A Dutch edited version of this paper will be published in a Dutch law magazine.

Footnotes

[1] A project initiated by the European Land Registry Association (ELRA), conducting research to identify an alternative process for foreign electronic purchases of immovables in countries, where registration of foreign deeds is admitted. See: www.elra.eu

[2]The Dutch chain integration program exists of three different parts: sending the requested information using XML-technology, automatic notifications (Watchdog) and the use of so-called stylesheets. See: www.kadaster.nl/kik (website available only in Dutch).

[3]The similarity with the medical sector emerges more often. On the 20th of November 1987, the Dutch Supreme Court (Hoge Raad) ruled that in a dispute between doctor Deutman and his patient, Mrs. Timmer, the doctor had to prove he did not make a mistake during surgery; the so-called reversed burden of proof.

[4] On the Internet there are a lot of do-it-yourself websites, e.g.: www.koopaktemaken.nl, www.doehetzelfnotaris.nl (websites only available in Dutch) or www.rocketlawyer.com and www.draftonce.com. These websites might take away (part of) business. Susskind describes it as “a commodity is an online solution that is made available for direct use by the end user (..)”, see: R. Susskind, The end of lawyers? Rethinking the Nature of Legal Services (Oxford University Press) at 32.

[5] On the other hand, access to information is not the same as legal advice. The context is equally important as the content. Furthermore, a great deal of information on the Internet – and perhaps an equally great deal of misinformation, as much of the information on the Internet is incomplete, outdated or simply incorrect.

[6] R. Susskind, The end of lawyers? at 2.

[7] Lawyers might be asked to prepare templates and general guidebooks that can be used by the clients themselves.

[8] At the north of the equator water turns right when flushing down the drain. At the Southern Hemisphere, the water turns counterclockwise. Standing exactly at the Equator, the water flows straight down the drain.

[9] The free movement of people, goods, services and capital.

[10] One could mention the Contract of sale, where the German Auflassung, the French Compromis de vente, the Dutch Koopcontract and the Spanish Escritura partly look a like but they are not the same because of the different legal results. Without pretending to be exhaustive, one of the (practical and legal) differences is that the Contract of Sale in the Netherlands is no more than the title to convey. To conveyance the immovable, a deed of transfer is mandatory in the Netherlands. In France and Germany the immovable transfers by concluding the Contract of Sale. In Spain the essential rule of the legal transfer of property is the título y modo (grounds of acquisition), followed by the traditio or delivery. (But there is the possibility to become owner by concluding the Contract of Sale with a clause concerning the transfer of possession).

[11] For example, the Directive 1999/93/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 1999 on a Community framework for electronic signatures.

[12] For example, the Regulation (EC) No 593/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 on the law applicable to contractual obligations (Rome I) as is explained in chapter 4.3 (footnote 36) and the proposed Regulation on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market as is explained in footnote 34.

[13] The legal system in the Netherlands more or less is a hybrid model, a semi-title system because of third-party- protection. The Cadastre registration is increasingly being trusted by different parties, especially since the Cadastre registration is one of the authentic registers in the Netherlands, see: ‘Authentic Registers in the Netherlands. ‘Technical ambition in relation to reliability and legal certainty’, J. Vos, in Annual Publication 4, ELRA 2011.

[14] ECJ, the 5th of February 1963 (case 26/62). The Court considered that provisions in the Rome Treaty may have a direct effect, if the text of the provision is fully clear and unconditional and there is no later need for a Member State to intervene to clarify the provision. If these conditions are met and the provisions have a direct effect, a citizen can invoke and use these provisions in a lawsuit before national court. Furthermore, the ECJ considered that the Member States did create an entirely new, supranational European rule of law.

[15] ECJ, 15th of June 1964 (case 6/64). The Court stated that (next to the fact that the Italian nationalization Act was not in violation of the EEC Treaty) European law takes precedence over national law, because European law demands an equal application within each Member State. The Treaty of Rome has created its own autonomous legal order.

[16]Cross Border electronic Conveyancing.

[17] Examples of difficulties, caused by hidden charges, limitations and overriding interests are enumerated in European Property Rights & Wrongs, edited by Diana Wallis MEP and Sara Allanson (Markprint, Lahti 2011).

[18] In 2009 a petition is presented to the Committee on Petitions from the European Parliament, Notice to members 19.06.2009 CM\785693EN.doc PE.426.967v01-00, see: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/peti/cm/785/785693/785693en.pdf

[19]The project was awarded with an action grant under the specific Programme Civil Justice 2010-2012.

[20] Consolidated version of Treaty on European Union 30 March 2010 (OJ 2010 C83/01).

[21] The Union allows freedom of People and Capital across borders with the objective of strengthening the union of the peoples of the EU Member States.

[22] EC 364/12 18.12.2000, which was given legal effect in the Treaty of Lisbon 2009.

[23] Regulation Rome I (EC) No 593/2008, 17-6-2008) and Regulation Rome II (EC) No 864/2007).

[24] Regulation on jurisdiction, applicable law, recognition and enforcement of decisions and acceptance and enforcement of authentic instruments in matters of succession and on the creation of a European Certificate of Succession (EC) No 650/2012, 04-07-2012.

[25] Just/2011-2012/JCIV/AG Paragraph 4.3 under 5 and 3.

[26] In the long term the CCRF could be developed as a basis for optional generic European digital conveyancing rules. For the short term the CCRF focuses on bilateral agreements with respect for existing legislation.

[27] Although it was a practical journey where the Registrars found themselves on the cutting edge, as can be deduced from some reactions from other organisations and critics (with the very useful help of the Academia) there was legal certainty concerning the practical implementation of European Regulations as will be described in the description of the practical case hereafter.

[28] In the case of Unibank/Christensen, on the 17th of June 1999 (case C-260/97), the European Court of Justice decided that an acknowledgment of indebtedness enforceable under the law of the State of origin whose authenticity has not been established by a public authority or other authority empowered for that purpose by that State does not constitute an authentic instrument within the meaning of Article 50 of the Convention of 27 September 1968 on Jurisdiction and the Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters.

The authentic nature of such instruments must be established beyond dispute so that the court in the State in which enforcement is sought is in a position to rely on their authenticity, since the instruments covered by Article 50 are enforced under exactly the same conditions as judgments.

[29] Quit recently the Spanish Supreme Court affirmed this ruling in Sentencia del Tribunal Supremo (España) STS No 998/2011, de 19/06/2012. See: http://www.poderjudicial.es/stfls/SALA%20DE%20PRENSA/NOVEDADES/28079119912012100007_STS%2 998_2011_escritura_aleman.pdf . According to the Supreme Court, a refusal of foreign deeds by the Registrar cannot be approved under the current understanding of the freedom to provide services at the European Union level; also, to require the involvement of a Spanish Notary would mean an unjustified limitation to the freedom of transfer of goods. Article 1462 of the Spanish Civil Code does not require that the deed be granted by a Spanish Notary. Therefore a formally valid deed granted by a foreign Notary will have the same effect (in terms of equation with delivery) as one notarized in Spain.

[30] It is known that a lot of English and German citizens are also buying (second) homes in Spain, especially at the coastal zone. By now we see an increasing interest in the Crobeco approach from citizens and expats. For example: http://www.expatmoneywatch.com/tag/expat-property-hell/ where the Crobeco-approach quite recently is appreciated, however the effectiveness is (wrongly) questioned.

[31] This Dutch Notary, Mr. Frits von Seydlitz, was already activitely advising Dutch (retired) people in Spain. Conveyancing immovable in Spain would be an extra opportunity for the Notary to serve (Dutch) people. He invested in his local network in Spain, hired servants who were familiar with the Spanish processes and language and was already speaking Spanish.

[32] A Certification Authority (or to use the exact terminology from the proposed European Regulation as mentioned in footnote 34: Trusted Service Provider) can issue qualified electronic signatures adding a so-called ‘attribute’ or ‘role’. For example, the role of a Notary, a bailiff or a lawyer. During the process of issuance, the TSP fulfils all kind of formalities. As a part of the issuing of a signature for a specific professional such as a Notary, he checks whether the Notary really is a Notary. But in daily practice sometimes notaries are being suspended. Whenever this is the case, the use of the signature should not be possible. But in the Certification Practice Statement (CPS) of TSP`s liability for the incorrect use is (mostly) excluded. This means the suspended Notary has to hand in the signature by himself. In other words, the TSP will not check whether the professional still is in function. The proposed Regulation does not repair this gap in the auditrail (yet). This might be a problem in Crobeco and in Eufides.

[33] ELRA asked other stakeholders to comment on the draft CCRF, receiving comments from, for instance, the Council of the Notariats of the European Union.

[34] This type of electronic signature has the same evidential legal value as a handwritten signature. The use of a qualified electronic signature (QES) is based on the European Directive 1999/93/EC. This Directive essentially covers electronic signatures only. Because there is no comprehensive EU cross-border and cross-sector framework for secure, trustworthy and easy to-use electronic transactions that encompasses electronic identification, authentication and signatures, the European Commission proposes a Regulation on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market. With this proposed Regulation the European Commission tries to fill the gaps left by the electronic signature Directive. It enhances and expands the acquis of the Directive. For reasons of legal certainty and clarity, Directive 1999/93/EC will be repealed, once the Regulation is accepted. The regulation aims to enhance existing legislation and to expand it to cover the mutual recognition and acceptance at EU level of notified electronic identification schemes and other essential related electronic trust services. As Registrars we need to be well aware of the identification-related and especially authorisation-related electronic credentials, required to secure electronic transactions (including ancillary services) and the changes that possibly need to be made.

[35] But it can just as easily be ‘Herrn Schmidt’ from Germany or ‘Mr. Smith’ from England. In fact, former Member of the European Parliament Mrs. Diane Wallis had compassion with a lot of (English) buyers, buying a house at the Spanish coastal zone. She deployed for this group for a long time and even published a book about the different issues foreign buyers have to deal with. The book is entitled “European Property Rights & Wrongs” and is based around contributions made on the namesake seminar. Please see: http://dianawallismep.org.uk/en/document/european-property-rights-and-wrongs.pdf.

[36] Article 3 of the Regulation on the law applicable to contractual obligations Regulation, as known as ‘Rome I’, (EC) No 593/2008. Admittedly, some restrictions are made in article 6 but these are not applicable in the case we describe in this paper. In the event of the seller being a professional (for example the construction company, who develops a new project) Mr. Smit is entitled to the consumer protection by the law of his habitual residence in the Netherlands. In the event of a seller who is not a professional, article 6 is not applicable.

[37] Article 23 of the Regulation on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgements in civil and commercial matters, also known as ‘Brussels I’, (EC) No 44/2001.

[38] The seller is obliged to transfer the sold goods free of all restrictions and special charges, “except those accepted explicitly by the buyer”. Notwithstanding any other stipulation, the seller vouches for the absence of charges and restrictions arising out of acts susceptible to registering in the Land Register, but were not registered at the time of the conclusion of the agreement.

[39] Article 14.1.b. of the Regulation on the law applicable to non-contractual obligations, also known as ́Rome II ́, (EC) No 864/2007.

[40] In the case of ECJ, C-618/10, Banesto c. Calderón Camino the European Court of Justice gave a ruling that Spanish law, giving the possibility to bring back an interest rate to an acceptable rate, is contrary to the Directive and therefore not allowed.

[41] It is a missuggestion that in England, because of the so called «buyer beware» principle, buyers should have to trace burdens by inspection of the property, as Mr. Wilsch has stated in: “Grundbuchrechtliche Probleme in Grossbritannien bei der Nachfolge in britische Immobilien”, ZEV 2011, 458, 461. Probably he has been mislead by the function of the English RPR (Real Property Report). This report indicates whether the location of all structures complies with municipal law but is not mandatory.

[42] Italy, France and Canada.

[43] The Cross-border Conveyancing Reference Framework as is explained in Chapter 4.1.

[44] The Registrars in some countries appear to attempt to take over the function of the Notary as it concerns the work done by notaries regarding real estate transactions. The fear for this takeover has been discussed during the 26th congress of the Union Internationale du Notariat, as can be deduced from a report of the congress, published in Weekblad voor Privaatrecht, Notariaat en Registratie (WPNR), No 6866, p. 895 – 896 and

No 6867, p. 930 – 933 (available in Dutch only).

[45] Perhaps that is why the Conseil des Notariats de l’Union Européenne (Council of Notaries of the European Union, hereafter: CNUE) launches a pendant of Crobeco: Eufides, a system of cooperation among European notaries in the area of real estate transactions. CNUE states that the aim of the Eufides project is to facilitate the circulation of authentic deeds, with complete legal certainty, by simplifying electronic cross-border processes. This aim certainly seems to be corresponding or at least have corresponding elements to Crobeco. Perhaps in future both project can get together as the aims are (more or less) the same and it even seems as if practice is similar as well, although there are some differences: Crobeco uses a fully electronical process (the Eufides website states that the transfer of data is almost done entirely electronically) and – perhaps more important – within the Eufides project parties need two notaries: they can contact their ‘regular civil law Notary’ and (s)he will get in touch with a Notary from the Member State in which the property is situated (Notary rei sitae). He or she will highlight the legal issues under the law of the place where the property is located, which will govern the contract (the Lex Rei Sitae). Crobeco is of a different mind (and approach): one of the cornerstones of the system of conflict-of-law rules in matters of contractual obligations (consideration 11 of the Regulation (EC) No 593/2008 is the freedom of the parties to choose the applicable law (article 3 of ‘Rome I’) should be the parties’ freedom to choose the applicable law. According to Article 3.1 the parties, by their choice, can select the law applicable to the whole or to part only of the contract. Therefore, it is possible to have Dutch law applicable regarding to Contract Law and Spanish law is applicable for Property Law. That is why a CROBECO-Notary needs to be familiar with foreign Contract Law. A Spanish Notary should become familiar with Dutch Contract Law and/or the Dutch Notary should become familiar with Spanish Property Law. If a Spanish Notary would like to pass a deed with Dutch Law as the applicable law, the Dutch Registrars or the CROBECO helpdesk could be of help. In practice it is the other way around, because of the amount of Dutch people buying houses in Spain and because people prefer their ‘regular civil law Notary’, it is the Dutch Notary who needs to be familiar with Spanish Property Law. It is up to the Notary to accept the help from the local Registrar or the CROBECO helpdesk.

[46] See footnote 44. In the report the reporter mentions “an ‘inhibitory effect’ of the double control on notarial efficiency” and “the idea of acquisition of the Land Registers by the notaries themselves”.

[47] See: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2010:115:0001:0038:en:PDF

[58] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:0171:FIN:EN:PDF

[49] Such as powers of attorney, proxies, payment receipts and in case of a legal entity the deed of incorporation.

[50] In the Dutch system the Notary is liable for any mistake (s)he made checking and scrutinizing the additional prove. The Registrar can rely on the thorough investigations by the Notary, although according to article 19 of book 3 of the Dutch Civil Code the Registrar is allowed to warn the clients of the Notary and third parties in case of legal impossibilities and unauthorized conveyancing, a competence the Registrar uses several times a year. The Dutch Registrar is liable for mistakes made recording the deed in the Land Register and adjusting the Cadastre registration.

[51] A good example of such a system is Landonline, a system introduced in 2003 in New Zealand. The production of any paper deeds in the registration process is dispensed with under this automated system. The Registry is a virtual registry, mandatory accessed by “ConveyancerConveyancers”, even though the manual system still exists for individuals undertaking private conveyancing. The Dutch chain integration project (www.kadaster.nl/kik, website only available in Dutch) is another example of an electronic conveyancing system. With this chain integration system, the Dutch notaries can maintain their editorial freedom for the majority of the deed. A small part of the deed has to be standardised, especially when compared to the European Certificate of Inheritance.

[52] Many public services are available online but their cross-border dimension has to be reinforced. Key in the strategy to improve such interaction is the development of Large Scale Pilot projects engaging stakeholders such as public authorities, service providers and research centres across the EU in the implementation of common solutions to deliver online public services and make them accessible throughout Europe. Run largely with and/or by Member States, the pilot projects develop practical solutions tested in real government service cases across Europe. These practical solutions will aid in making crossborder government services a reality. They will ensure that government administrations of different countries in the EU can speak to each other digitally despite different national technical specificities and languages. Five LSPs are on-going: e-Codex (www.ecodex.eu), epSOS (www.epsos.eu), STORK (www.eid-stork.eu), PEPPOL (www.peppol.eu) and SPOCS (www.eu- spocs.eu) to support interoperability of services and as a consequence, the mobility of citizens and businesses.

[53] This might be by using a Certificate Revocation List (CRL): a list of certificates to which the encryption

key might have come into the possession of unauthorised parties. It could also be by using an OCSP (Online Certificate Status Protocol): an Internet protocol used for obtaining the revocation status of a digital

certificate.

[54] The European Commission firmly focuses on the free movement of documents, as is demonstrated by the abolition of the exequatur, as it is (one of) the foundation(s) of the so-called “Brussels I” Regulation. On the 6th of december 2012 the Council adopted the recast of a regulation on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters.