January 1, 2013 / Ruben Roes

In the Netherlands, Cadastre and Landregisters are integrated. The information in the Cadastre registration is derived from the deeds in the Land Register. The Cadastre provides access to the Land Register. The registrar is responsible for as well the Land Register as the Cadastre.

Background

Public data is administered by a number of government agencies that are referred to as ‘source holders’. The current situation is the result of historical factors related to the original primary objective of registration. For example, the registration of land was started for tax-collecting reasons, which is why until 1973 land registration was carried out by the Ministry of Finance. This work was then transferred to the VROM (Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment) but since 1994 it has been the Kadaster (the Land Registry), an independent administrative body that is part of VROM 2, which has been responsible for recording legal and geographical information on real estate properties.

There are other source holders in addition to the Kadaster. For instance, the municipal authorities are responsible for recording address data and personal data, whereas the Chambers of Commerce are responsible for registering information on legal entities.

The system of key registers was set up because members of the public had to keep on giving the same information to one government agency after another, which created a great deal of administrative (paper)work and ‘red tape’. The new system of key registers means there are now a number of government agencies whose data on specific subjects is deemed to be authentic. Other authorities and government agencies are then obliged to use this authentic information when carrying out their own registration processes, so that members of the public do not have to keep on providing this same information.

The implementation of this so-called ‘key register system’ has led to a huge increase in the need to link data between different registers. Nowadays, data from separately administered registers can be combined, allowing interested parties to see at a glance relevant information on plots of land that supplements the legal and geographical information that the Kadaster’s registrar is responsible for.

This means that although the cadastre and the information the Kadaster’s registrar issued used to contain private-law data only, nowadays the information that the Kadaster key register provides alsoincludes relevant information on specific public-law decisions. This is achieved both by linking up with a nationwide register where municipalities link there information with land registry plots and by non- municipal authorities filing copies of their decisions directly in the Kadaster’s land register.

Furthermore, technological developments mean that nowadays there are additional options for linking data. The increasing digitisation of information means that this data can now be combined efficiently, whereas combining information held on paper involves much more work. The deployment of geographical technology means that information from the key register can now be recorded in more precise detail (for example by recording areas’ geographical coordinates), something that ultimately improves the quality of the legal information provided.

Responsibilities

When combining data with data from other registers, there are some important legal questions to ask (and answer), namely:

Who is liable for data that is inaccurate or lacking?

Who is responsible for information issued by the cadastre that contains data from other registers?

Before answering these questions, I will first outline a Dutch example regarding data-combination, namely the information on government decisions that contain public-law restrictions.

Information on government decisions that contain public-law restrictions

In the Netherlands, not all data on government decisions that contain public-law restrictions is registered in the same way.

Firstly, a procedure exists whereby municipalities can record their own decisions in their own register.

In the Netherlands, there are a total of 415 municipalities that record public-law restrictions in their registers as part of a joint National Facility (the ‘Landelijke Voorziening WKPB”) that records information on land registry plots. This work is undertaken under the WKPB Act (Wet kenbaarheid publiekrechtelijke beperkingen/Act on the Recognizability of Public Law Restrictions). The WKPB Act explicitly states that the responsibility for the correct link between restriction and land registry plot lies with the municipalities. When cadastre issues information, the data on public-law restrictions from the WKPB national facility is added but is expressly not copied to the data in the cadastre. This prevents the registrar of the Kadaster from being held liable if the municipality has linked a decision to the incorrect land registry plot.

In practice this process doesn’t work properly. One of the main reasons is that it takes too much time for the municipalities to update the data. They get a dump of all the cadastral parcels that have got new numbers, and then they have to inquire which parcels contain public-law restrictions and bring over the public-law restrictions to the new parcels. The minimum time to update the register will then be about one month.

Big municipalities, like the city of Amsterdam, investigate whether it is possible to end this situation and get a reasonable alternative, for example recording their decisions regarding public-law restrictions directly at the land register and the cadastre of the Kadaster.

Secondly, there is also a procedure whereby non-municipal authorities can register those of their decisions that contain public-law restrictions directly in the Kadaster’s land register. This registration can be undertaken in one of two ways. The administrative body can submit the decision for registration, including details of the land registry plot that the restriction relates to. Normally, the area covered by the restriction will not correspond exactly with the boundary of the land registry plot. Consider for instance a decontamination decision related to ground pollution. The area of ground pollution will not be delineated precisely by land registry plot boundaries. Note that the disadvantage of this approach is that in the event that the land registry plot is subsequently divided up – something that is a regular occurrence in a densely populated country such as the Netherlands – it will become unclear whether the government decision applies to all the newly created plots. The only course of action now open to the registrars is to err on the side of caution and state in the note on the government decision that it applies to all the newly created plots. In this way, a type of land registry ‘contamination’ takes place, whereby a decision is recorded as applying to far more land registry plots than just the land registry plot to which it actually applies. Since the registrars want their registered entries to correspond as closely as possible to the legal reality, an administrative process will then be launched to ask the relevant government body to clarify whether the decision applied to all the plots. This is clearly a cumbersome approach to take, especially when you consider the additional costs and administrative work involved and the out-of-date nature of the resulting data.

The above situation was the reason why a new procedure known as the ‘contours procedure’ was created, which procedure also prevents the above land registry ‘contamination’ from occurring. Under the new procedure, the geographical coordinates of the contours for the area that is subject to the government decision are registered too. Recording the coordinates in a separate layer under the land registry map means you can see precisely whether all the new plots created when a particular plot was divided up are subject to the public-law restriction. If it turns out that the area covered by the restriction is not part of the new land registry plot then details of the restriction will not be included in the entry for that new plot.

The following example illustrates this:

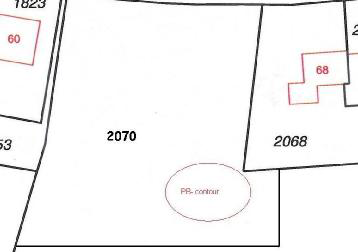

Ground pollution (marked by a circle) has been found on plot 2070.

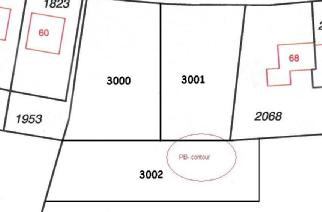

Plot 2070 has to be split into 3 new land registry plots, which are indicated as numbers 3000, 3001 and 3002.

If contours were not used then the entry on ground pollution would have to be included in the entries for all three of the plots 3000, 3001 and 3002.

In contrast, if contours are used then the entry on ground pollution only has to be included in the entries for the plots 3001 and 3002.

PB-contour = contour showing area covered by public-law restriction.

There are two stages to the contours procedure, namely:

- the filing phase (pre-registration) and

- the actual entering and registration of the data.

The filing phase

During this phase, the area covered by the public-law restriction is indicated using graphical coordinates and lines and the data is sent to the registrar. The registrar no longer simply files away the coordinate data – instead, he now checks that the contours have been linked with the correct land registry plot. He does this by projecting the coordinates under a layer of the land registry map, so that it can be seen which land registry plots the contour relates to.

In fact, the actual projecting of the coordinates under a layer of the land registry map is not done by the land registrar himself. It is done by employees from a central unit who are well-educated and have a direct mandate from the land registrar. The software they use is regarded as “reliable” by an IT- auditor. These are two very important preconditions that the land registrar will determine.

The map that shows the contour is then prepared and filed in a preregistration deposit. The party submitting the information can now check whether the contour is correctly located on the land registry map. Does the contour run through the correct land registry plots that where mentioned in the government’s decision? If it doesn’t, the party amends the coordinates issued and submits an application for an amendment to the registrar. If the contour is correct then the party needs do nothing, and the coordinates together with the contour map remain available in the preregistration deposit in unaltered form.

The contour map will get a preregistration number that is communicated by the registrar to the supplier of the data. If the registrar gets a request from the supplier (government) he will link the contour map to the public-law restriction that is recorded in the so-called registration phase.

The registration phase

During this phase, the government decision regarding the public-law restriction is submitted to the land register for registration. This submission refers to the contour on the land registry map that was taken in the preregistration deposit, by referring to the preregistration number. It is no longer necessary to explicitly name the land registry plots, as they are now depicted on the contour map. Note too that the decision will expressly state that the registration will be updated based on the contour map that is included as an annex to the registered document. In the cadastre, the public-law restrictions are linked directly to the land registry plot in question with a brief description. Only the current restrictions are shown. If a new registration shows that a previous public-law restriction has to be replaced by a new one, only the new one will be shown as current data.3

Afterwards, the land registrars organize quality checks to be sure that the preconditions are implemented and enforced correctly.

Principles and guidelines

In the example, while the registrar is not personally responsible for the inaccuracy of data from another source holder, he is at risk of being liable because the other source holder’s data is incorrectly linked to the unique cadastral identification source: the cadastral parcel. The degree of responsibility differs in the various examples, but it is present to a greater or lesser extent in all cases.

For this reason, Dutch registrars always adhere to a number of principles when linking data from the cadastre to data from other sources. When using information from other registers, it is necessary that the principles used guarantee legal certainty in all cases. These principles can be described in a way that also allows guidelines for registrars to be formulated with respect to fulfilling their responsibilities for issuing information.

Principle: the principle of consent.

Guideline: Put registrars in charge when combining the information to ensure that the principle of consent is satisfied. Registrars must be able to draw up the preconditions for using the information, perform quality checks under their responsibility and maintain these preconditions by giving instructions to surveyors or others who provide the information.

The principle of consent

This is one of the general principles of land administration. The principle of consent implies that the actual authorised person who is listed as such in the land administration must give his or her explicit consent for changing an entry in the land administration. This is tied to the essence of ownership. Ownership is the most comprehensive right to a parcel. This right may not be limited without the consent of the parties involved.

The principle of consent is very important when combining data and can apply to both private-law rights (for which it was originally intended) and public-law rights.

JBN 2006(12) 70 De Wet kenbaarheid publiekrechtelijke beperkingen onroerende zaken (‘Act on the Recognizability of Public Law Restrictions on real estate’)

‘Towards a more positive system of land administration’ (in Dutch).

Under private law, a consensus between parties is always necessary to bring about private-law limitations to the ownership. For example, a right of usufruct does not arise due to the one-sided interests of the usufructuary, but as a result of a consensus between the owner and usufructuary. In the Dutch legal system, this consensus translates itself into the registration of notarial deeds in the land register. In this way, the owner and usufructuary determine the object upon which the right of the usufruct is established, among other things.

In addition, the principle of consent can also apply in situations that pertain purely to public law. This requires a somewhat broader interpretation of the concept of consent. In the public-law situation, the owner does not by definition agree to the government decision concerning his parcel, but the decision has been made after a careful decision-making process involving the owner. In the case of a dispute, an independent court assesses the legitimacy of the government decision. An example would be a government decision indicating the presence of soil contamination on a parcel in which the government obligates the owner to resolve this and clean up the soil. The owner is not required to agree with this decision. However, in a democratic society, such decisions are made in a procedure that involves the owner and in which he has the opportunity to present his view to the government.

The government then makes a decision based on democratically established laws and rules (which have been consented to by the majority of society). If the owner does not agree with this, an independent court can assess its legitimacy.

If this government decision is later declared to apply to parcels which were never involved in the decision-making process, this would violate the principle of consent.

This is exactly what happens when government data is incorrectly linked to cadastral data; parcels are simply assigned an entry indicating that they are contaminated, and the owner is left to deal with all the adverse effects of this.

In order to prevent this, it is important that the legal practitioners are in charge when this information is used. They must be able to draw up the preconditions for using the information, perform quality checks under their responsibility and maintain these preconditions by giving instructions to surveyors or others who provide the information.

It is therefore essential that, when displaying WKPB contours of government decisions on the cadastral map, the registrar sets the preconditions for including the geographic information into the cadastral map. This includes verifying in advance whether the data of the contour corresponds with the cadastral parcel information of the government decision (as it is presented to the public).

As previously mentioned, for municipal decisions in the Netherlands there is a national facility for handling the Disclosure of Public Law Restrictions Act (LV WKPB) in which the government decisions are entered. The responsibility for correctly linking this data to cadastral parcels does not lie with the registrar. Based on an explicit provision in the legislation, the responsibility for this lies with the municipalities, while the registrar still has to contribute the data from the cadastre. This is a potential risk for the registrar and will decrease legal certainty. This usually goes smoothly during the first inclusion in the register, and the municipalities make an entry for the cadastral parcels as they are listed in the government decision. Problems can arise during follow-up transactions and the division of cadastral parcels involving renumbering. It is not possible for registrars to check which new parcels are impacted by the government decisions, it takes a long time before municipalities update their data in this regard and checks by the public are not possible. This diminishes the up-to-datedness and reliability of information on government decisions and damages society’s confidence in the information provided by the registrar. It is an undesirable situation which also chafes against the principle of consent.

Principle: the principle of trust

Guideline: Let’s use information technology to enrich information, but subordinate IT to legal demands in order to ensure the principle of trust.

The principle of trust

The principle of publicity is a well known general principle of land administration. It is sometimes mentioned as the principle of good faith. It implies that the legal registers for public inspection are vouched for and that third parties can, in good faith, treat the information as more or less correct such that they are protected by the law. So the principle of publicity / good faith is basically a private-law principle. But it is also important that when data is combined with data from other registers the end product can still be treated as correct. So when data of the cadastre is combined with public law it is also important that third parties can rely on that information. Because it is not exactly “good faith” in its private law form (the public limitations are valid even if they are not registered) I would call this the principle of trust. It means that the public law restrictions are registered so accurately that third parties can actually rely on the information in the cadastre.

Enriching the information by combining data is an attractive alternative and has the potential to enormously enrich information on legal certainty. It also makes it possible to provide the public with better information about their property because the information is concentrated, obtainable via a one- stop shop and more readily available online. It undoubtedly satisfies a growing need of society and offers fantastic possibilities. It is also a development that is inevitable. Clear the way for innovative technology!

But there is also a flip-side. There is a risk that combining data will be elevated to a goal in itself, while the guaranteeing of accurate information becomes less important. Certainly in our modern society with Google and ‘wiki’-based websites, there is an opportunity for everyone who wants it to add data to information in order to make the information more expansive and readily accessible.

If we are not careful, a similar kind of situation will arise with respect to combining data with the cadastre, and the reliability of the data will suffer. The cadastre will then become a kind of Wiki- register in which everyone who wants to add something can and the accuracy of this information will no longer be guaranteed. Meanwhile, the public will also be given the false impression that simply because data has been added means that it must be true.

In short, it must be ensured that the information being enriched is genuine. This is only possible if clear legal demands are made with respect to the combination of data. IT will only be used if it satisfies these conditions – otherwise not.

The registrars are by definition capable of ensuring this, especially because they can determine the unique linking points and how these relate to the unique cadastral linking point: the cadastral parcel. What’s more, the registrars can take into account how the information to be linked was gathered and to what extent the title holders were in one way or another involved in this. Also they can set preconditions such as the fact that they can mandate employees who combine the information directly and take care of the fact that the software they use is regarded as “reliable” by an IT-auditor. This principle does not only apply to IT. Perhaps in the future, a similar kind of situation will arise with respect to the acquisition of data in the land surveying process. If the owners of parcels themselves would be capable of determining a cadastral boundary by using coordinates that are directly adjustable on the cadastral map, they would be able to enrich the property registration process. Here, as well, proper preconditions would have to be set with respect to verification using data from the land register, the quality of the geographic data and the authentication and authorisation of the parties involved. This is another area in which the land registrar can play a key role.

Final conclusion

If cadastral information is provided after data from other registers has been adopted for cadastral parcels, or the corresponding rights and title holders, the responsibility for the decision to adopt this data will lie with the registrar. It is increasingly clear that the connection between the cadastral parcel and the other data is essential, and must be guaranteed as correct. At the moment the registrar wants to enrich data with data from other sources, he must be certain that the connection is correct so that data can be shown. A passive role for the registrar in this process would not be appropriate. The registrar is charged with protecting members of the public against claims of others which are wrongfully attributed to their property. This can also mean protecting them against the government. Authorities have a tendency to underestimate this and see a registrar who sets preconditions to connections as a nuisance. However, the government will also have to realise that if the registrar’s role here is devalued a devaluation of the legal certainty will not be far behind. The government will also have to realise that legal certainty is the priority in the application of new technology, as IT must be subordinated to the legal demands. The moment at which the reverse is the case is the moment at which the land registrar has to stand up and draw a line to protect legal certainty.