January 1, 2011 / Aileen McHugh

This paper is dedicated to those staff at the Irish Property Registration Authority who retire during 2010, in particular Diarmuid Clancy, Michael Treacy, Fran Leahy and Paul Brent, members of the Senior Management Team who contributed, in a very significant manner at a strategic level, to the transformation of Irish property registration services.

Introduction

This article describes the development of property registration in Ireland from its genesis over three hundred year ago, as initial deeds based system when Ireland was under English rule, to its evolution over the past two decades into a modern, technologically based public sector organisation. A land registry is an enabling institution emblematic of a free society. Property registration cannot be viewed, therefore, in a legalistic vacuum devoid of any consideration of economic, social or political factors. Indeed, it could be said that the benefit proposition of property registration is both legal and economic. Manthorpe (2007) emphasised that registration must operate within the rule of law and human rights. Pollitt and Bouckaert (2004) contend that public management is not a neutral, technical process, but an activity closely and seamlessly interwoven with politics, law and the wider society. This article, therefore, explores the historical background and the current social and economic context pertaining to the Property Registration Authority (PRA), which was established in 2006 to administer both the Land Registry and Registry of Deeds in Ireland. The governance and technological innovations which have already taken place in the organisation are also outlined.

The transformation of property registration services in Ireland is a process which resonates with parallel paradigmatic shifts in theories of public management from traditional public administration through New Public Management (NPM) to more recent articulations of networked governance, citizen-centric services and Public Value. In conclusion, therefore, this paper looks to the future in terms of initiatives in relation to the growing impetus both nationally and internationally towards networked and digital era governance and its relevance to the unique and valuable spatial and ownership datasets now under the control of the PRA.

Irish property ownership propensity: the historical context

The Irish have demonstrated a propensity to buy property and home ownership rates in Ireland are among the highest in the EU. The 2006 Census figures confirm that owner-occupation, at 74.7%, continues to be the most prevalent housing occupancy status (CSO, 2006). This ownership preference has deep historical and sociological roots in Ireland’s colonial past and it is appropriate to reflect on the Irish propensity and desire to own property in the light of historical dispossession of lands and displacement of owners by the English conquerors. For instance, following the Williamite wars of the seventeenth century more than three quarters of the land of Ireland was expropriated. (APOCC, 2004). Evictions of tenant farmers carried out later during the famine years 1845-1848 are also deeply embedded in folk memory and culture and in the Irish psyche.

Wylie’s (1986) division of the history of Irish land law into five main eras provides a useful thumbnail of the trajectory of property ownership in Ireland through the centuries:

- Pre -Twelfth Century – Ancient Irish /Brehon Law

- 12th -17th Centuries – Introduction of English Common or Feudal law

- 17th-18th Century – Confiscation and re-settlement of Irish land by the English; Establishment of Registry of Deeds

- 19th Century reforms – beginning of the resolution of the land problem; enactment of Land Purchase Acts; Establishment of Land Registry

- 20th century – carrying through of earlier reforms, rapid growth of state intervention and public control over the use of land

State intervention has played a pivotal role in the growth of home ownership. According to Fahey et al (2004) -“A number of strands of public policy were central to what was in effect a revolution over the course of the twentieth century that changed Irish households from being predominantly renters at the beginning of the century to predominantly homeowners at the end.”

Initiatives included the rural land reforms, which continued after independence was achieved, and the policy of tenant purchase of local authority housing so prevalent in urban areas in the 1970s and 1980s, which was originally initiated in the 1930s in rural Ireland.

Genesis of Irish property registration system

The Registry of Deeds was established in 1707 and its main function was to combat fraud and forgeries in land transactions by establishing a system for determining priority between documents relating to the same piece of land. While registration did not guarantee ownership of land, it meant that a registered document took priority over later registered documents and documents that had not been registered. The historical context of the Act, the introduction of the infamous penal laws in the early 18th century which included far-reaching restrictions on the ownership and acquisition of land by Catholics, is evident in its introduction, where it states that forgeries and fraudulent gifts were frequently practiced «especially by Papists to the great prejudice of the Protestant interest …»

The Land Registry was established in 1891 and, unlike the Registry of Deeds, it is a register of land ownership. Here again, the historical context of the Land Purchase Acts is all important. Loans were advanced to tenant farmers to purchase their holdings from landlords subject to annual repayments in the form of land purchase annuities. As these schemes involved the advancing of large amounts of public funds, it was considered that title to the lands in question, which formed the security for the loans and which might have to be sold in the event of default, should be secured by means of registration. Registration of actual ownership of land in the Land Registry is superior to the registration of deeds in the Registry of Deeds. Government policy on Compulsory First Registration will ultimately lead to the closure of the Registry of Deeds and thereby facilitate progression of eConveyancing.

As a direct consequence of the 1891 Registration of Title system most agricultural land is now registered. Land mass coverage generally in terms of registration in Ireland is therefore comparatively high at 93%, representing about 88% of all legal titles in Ireland. It is noteworthy that in fifteen counties (out of twenty six) 98% of titles are registered. While unregistered titles are very rare over much of the country, many of the titles that remain unregistered relate to particularly valuable commercial and residential properties located within urban inner-city areas of the two largest cities Dublin and Cork (O’Sullivan, 2007). Completion of the register is government policy and since 1 January 2010 compulsory registration has now been extended to all counties with the exception of Dublin and Cork.

Property cycles and Government intervention: impact on registration system

Property cycles and government interventions have inevitably affected and continue to affect the pattern of intake of applications for registration. After independence, from 1921 onwards, there was a largely rural ethos in Ireland. Urbanisation was slow to develop in contrast to Europe and America, where cities had grown enormously since the nineteenth century. Only since the mid 1960s has more than half the population of Ireland lived in towns, the catalyst for which was the First Programme for Economic Expansion 1958 (APOCC, 2004). Economic revival and activity brought with it a need for property markets with their own unique cyclical features, the effects of which have been keenly felt in the past two decades.

According to the National Economic and Social Council (NESC) the net increase in employment between 1993 and 2003, a cumulative 43%, exceeded the increase for the rest of the entire twentieth century. This phenomenal and concentrated period of employment growth created a sharp increase in the demand for housing. Irish average income levels had been around two thirds of the EU average and were declining in relative terms before the 1960s. Over the 1990s, however, average incomes in Ireland converged with the EU average. In addition Fiscal policy influenced the level of aggregate demand for housing since 1987 in two major ways. Firstly, the tax take from personal income was reduced and disposable incomes grew faster than gross incomes. Secondly, budgetary policy was particularly benign to those on higher incomes, fuelling demand for luxury homes, speculative investment and holiday homes. (NESC 3/2004)

Following 2000 there was a slowdown in economic growth in the global economy and in Ireland. However, there continued to be a strong demand for housing which has been explained as unmet demand in the boom year and also attributed to government tax incentives, which came into play from 2001 onwards. These incentives contributed to overheating of property prices and construction, resulting in inventory overhang by 2007. Inevitably, in the perfect storm economic conditions prevailing worldwide at this point, a property crash resulted which has devastated the Irish construction industry. An eminent Irish historian put the Irish asset bubble years in historical context as follows:

“.the last decade has witnessed one of the greatest ironies of Irish social history. The Irish social revolution of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, in which the political and social power of the landlords was broken by their tenants, was replaced one hundred years later by a native class of landowners, speculators and bankers who exercised their domination of land and the property market in an even more invidious way than some of the most wretched 19th century landlords. The political and economic establishment facilitated and encouraged them throughout the last decade.” (Ferriter, 2009).

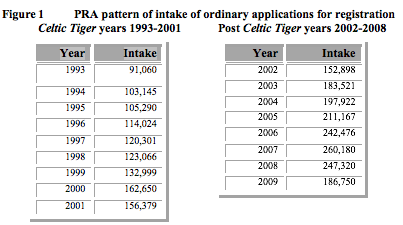

The factors at play in the Irish economy from the early 1990s onwards greatly influenced the rise in Intake to the PRA for which, at the time, it was ill-prepared. Figure 1 shows the pattern of intake from 1993 to 2009 and is divided into two distinct periods. The first is the Celtic Tiger era of export led growth and the second the fiscally fuelled asset bubble years from 2001 onwards.

Figure 1 PRA pattern of intake of ordinary applications for registration

During the Celtic Tiger years 1993-2001 intake of dealings grew by 71.73%. It is noteworthy that there was a drop in intake of 3.8% between 2000 and 2001, when the economic downturn initially commenced. However, this was a short lived decrease and between 2001 and 2007 there was a further increase of 66.37%, despite the slowdown in economic growth. This was fiscally driven by ill-judged Government tax incentives. By 2009 there was a decrease in intake of 28% over 2007 reflecting fallout from adverse worldwide economic conditions and the Irish banking crisis which resulted in the collapse of an overheated construction industry.

A wider ownership base, and an aging demographic profile in this base, will ensure continuing intake of non-sale transactions including transmissions on death of existing registered owners. Inevitably judgements, powers of sale and bankruptcies consequent on the economic downturn will also increase. However, overall intake levels will inevitably decline for the duration of the current recessionary period.

Programme of modernisation in the PRA

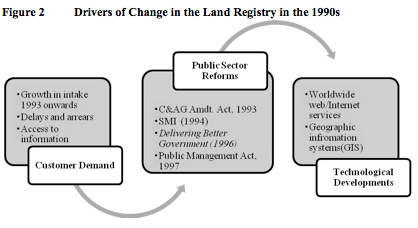

The exponential increase in intake of applications due to the unprecedented growth in the property market from the 1990s onwards was but one significant factor driving change. In common with other government bodies, the drivers of modernisation illustrated in Figure 2, related to not just customer demand, but also to public sector reforms and to technological developments.

Figure 2 Drivers of Change in the Land Registry in the 1990s

Irish public service reform initiatives in this period included the publication by Government of a landmark reform document ‘Delivering Better Government’ (DBG, 1996) and the introduction of the Strategic Management Initiative for all Government offices and agencies (SMI). This was the Irish equivalent of the New Public Management reforms then sweeping through the Anglo-American democracies e.g. US, UK, Australia and New Zealand. Allied to this was the enactment of various pieces of legislation including the Public Services Management Act, 1997 and the Freedom of Information Act, 1997.

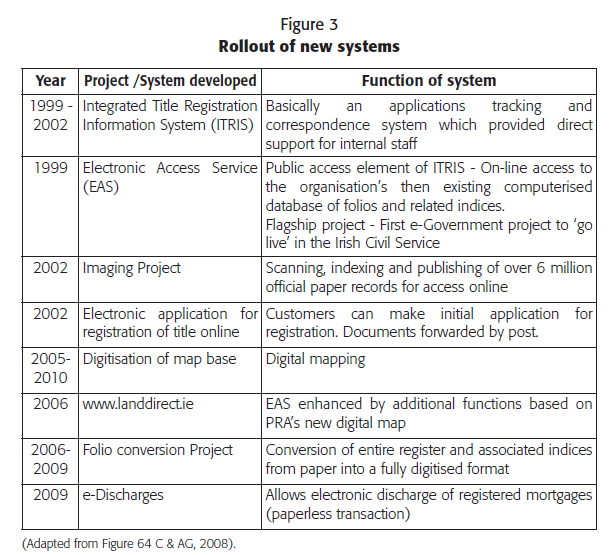

The commencement of the process of modernisation in the Land Registry can be traced back to 1992 and to the vision of its then, newly appointed Registrar and now CEO, Catherine Treacy. Together with her senior management team and staff, she has overseen a huge programme of reform encompassing continuous overlapping change initiatives. In 1992 a Strategic Plan encompassing thirty two projects was prepared which for the first time aligned a set of ICT projects and a clear delivery timetable with the business objectives and service delivery requirements of the organisation. (Treacy and O’Sullivan, 2004). Figure 3 shows the gradual rollout of some of the more important major new systems and major projects undertaken since 1999.

Figure 3 Rollout of new systems

Kennedy et al (2009) noted that the CEO and her management team ‘led from the top in terms of providing leadership and vision’ in relation to these change initiatives. They also concluded that- ‘The key organisational benefits achieved include increased efficiencies, productivity gains and reputational benefits for the entire organisation’.

In August 2004 a document imaging project was successfully completed. As a result all paper folios and maps were converted into electronic records available on-line to account holders. Over 6.5 million pages of records were scanned indexed and made available electronically. The Digital Mapping Project, which commenced in 2005, was a five year project of immense complexity and is on track to be completed in mid-2010. It has involved the digitisation of 2.2 million land parcels, which were hitherto contained on 36,000 paper map sheets (Treacy and O’Sullivan, 2004). In 2006, the PRA outlined its eRegistration vision to incrementally extend the range of applications which can be registered without the presentation of paper documents to the Authority. Rollout commenced in April 2009 with eDischarges, whereby mortgage entries on the register can be cancelled by financial institutions themselves. This project has proved hugely successful and within six months following commencement, virtually all the major lenders had availed of the new service. eDischarges will be followed in due course by online registration of mortgages, full transfers of ownership, transmissions on death and other types of registration. In a report prepared by BearingPoint for the Irish Law Reform Commission (LRC) in 2006, stakeholders in the overall eConveyancing process viewed the development of an eRegistration capability as central to future conveyancing reform (LRC, 2006)

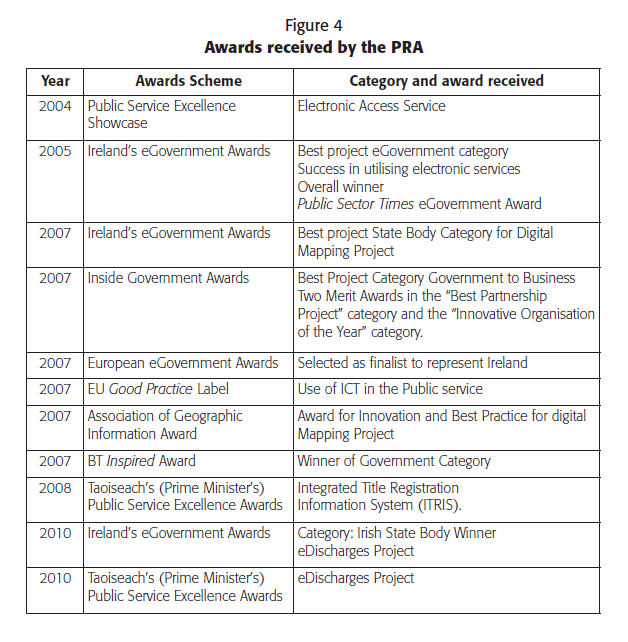

External Validation

The PRA has been to the forefront in the Irish public sector in its adoption of information communications technology, as is evidenced by the number of national awards and international recognition received by the organisation in recent years. It has also succeeded in bringing all major projects to fruition on time and within budget. Relatively speaking in terms of ICT projects, whether undertaken in the public or private sector, the record of the PRA has been exemplary.

Figure 4 Awards received by the PRA

In the Comptroller and Auditor General’s Report on eGovernment in October 2007 the PRA received favourable mention –

“In some areas of the public service – for instance Revenue, the Department of Social and Family Affairs, and the Department of Agriculture and Food, as well as in smaller agencies such as the Property Registration Authority and Ordnance Survey Ireland – the opportunities offered by the new technology for business transformation and for meeting consumer demand were well recognised and largely addressed. In some other public service providers, it was not clear that the opportunities were as well recognised” (C&AG, 2007 pg. 11)

Kennedy et al (2009) concluded that through the use of IT as a catalyst and enabler of organisational process redesign that the Land Registry –“has effectively reinvented itself from an inflexible, slow, labour intensive service to an efficient, speedy and customer centric one” Productivity and response times have improved greatly through judicious use of technology and historic arrears are on track to be more or less eliminated by the end of 2010. Even more significant is that the success of digital mapping and eDischarges, in particular, has built confidence in the concept of eConveyancing among stakeholders.

New Authority

Politically led innovation quite often entails alteration of existing governance structures, an example of which is the establishment of the Property Registration Authority in 2006. The main functions of the new Authority are to manage and control the Registry of Deeds and the Land Registry and to promote and extend the registration of ownership of land, building on the modernisation programme already underway in the registries. The members of the Authority are representative of the main users of land registration and related information services. The PRA is a hybrid state organisation in that the Authority is not merely an advisory board, and as such, the members exercise the role of “registering authority” in relation to property registration in Ireland. This role was exercised by the Registrar of Deeds and Titles under the provisions of the Registration of Title Act, 1964. The title of ‘Registrar’, as such, no longer exists. The 11 member Authority comprises representatives from the Law Society, the Bar Council, the financial institutions, the Department of Justice, PRA staff and also includes representatives of sectors including farming, accountancy and ICT.

The Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform, in his contribution to the Second Stage of the Registration of Deeds and Title Bill, 2005, stated that the new Authority was being established by Government as a mechanism to increase the visibility and profile of property registration services in Ireland. It was also intended that the composition of the new Authority would bring stakeholder expertise to bear in the discharge of its functions The new structure is intended (1) to facilitate stakeholder involvement in the strategic management and modernisation of registry services; (2) to provide channels of knowledge of, and feedback from, the conveyancing and property sectors, leading to increased responsiveness to customer needs and ensuring quality customer service and (3) to make commercial and business expertise available to the new Authority to ensure cost effectiveness ( Dáil Debates, 2005 ).

Future Directions

With digital systems and knowledge management principles assuming greater significance for Irish property registration services, disciplines, other than the purely legal, will increase in relevance over the coming years. Fresh opportunities and unanticipated risks will inevitably arise through progression of the eConveyancing agenda and also from collaborative data management. Changed capacities, relationships and roles will also evolve necessitating inter alia the ongoing development of expertise, innovative tools and metrics. Opportunities for new services, agency merger, data harmonisation and strategic partnerships are now accessible to offset decreasing fee income arising from declining intake. One of these opportunities relates to taxation.

Buoyancy in the property market in a period of economic slowdown from 2001 onwards led to increasing fiscal dependence on property transaction related receipts from VAT, stamp duty and capital gains. However, since 2006 the deterioration in the public finances has been rapid as house prices and sales have declined. In addition there has been an increasing threat to employment and corporate tax receipts as globalised conglomerates decide to close/relocate their Irish plants elsewhere. Unfortunately, the total tax take by the Irish exchequer at 34% of GDP, is lower than the EU average of 42.9% which means that fewer monies are available for public services (Eurostat, 2008). Inevitably arguments relating to the imposition of increased taxation and new forms of non-transaction related property taxation are now coming to the fore. In particular, it is now Government policy to introduce a site value tax, which was referred to in the Budget speech by the Minister for Finance in December 2009 as being developed in conjunction with property registration (Budget, 2010).

Another opportunity relates to agency merger. The Report of the Special Group on Public Service Numbers and Expenditure Programmes (McCarthy, 2009) recommended that the Valuation Office, Ordnance Survey Ireland and the PRA be amalgamated. However, there has yet to be a Government decision on this matter.

A third opportunity may lie through formation of strategic partnerships. The completion of the Digital Mapping Project in 2010 will result in the Authority having custody and control over valuable ownership and spatial datasets. Compulsory registration will drive the asset management policies of major utilities and local authorities and collaborative networks could be established in this regard. A recent development also has been the initiation by Government of discussions amongst a number of bodies, from both private and public sectors, in relation to the establishment of a national house price register. Timely information is no longer forthcoming from the financial sector, as too few mortgages are now being issued to facilitate publication of accurate data.

In addition, there is an increasing emphasis worldwide on the concept and value of spatial data infrastructure (SDI) to facilitate inter and intra-jurisdiction spatial data sharing. Rajabifard et al (2002) describe SDI as fundamentally about ‘facilitation and co-ordination of the exchange and sharing of spatial data between stakeholders in the spatial data community’. SDI may therefore be defined as an initiative intended to create an environment in which all stakeholders can co-operate with each other and interact with technology, to better achieve their objectives at different political/administrative levels. An SDI can be seen as basic infrastructure, like roads, railways and electricity distribution, which supports sustainable development, and in particular economic development, environmental management and social stability. The principle objective for developing SDI is to achieve better outcomes from spatially related economic, social and environmental decision-making. Of relevance in this regard to the PRA are the EU Inspire Directive and the Irish Spatial Data Initiative, established under the auspices of the Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government. According to Mohammadi et al (2010) the development of spatial data integration is dependent on overcoming hurdles in relation to interoperability of data systems and related technical, legal, institutional, policy and social barriers. Typically a national SDI would have a policy vision, an institutional vision, a legal vision, a technical vision as well as an overall vision.

Conclusion

This article has traced the transformation of Irish property registration services from their inception in a historical context of dispossession in the 18th century to the digitisation of its spatial and ownership information databases in the 21st century. It has been shown that, over the last two decades, in particular, the image and reputation of the organisation has been palpably enhanced through internally generated modernisation and externally through the establishment of the new Authority. Over time the PRA has gained more confidence in relation to its role, the benefit proposition it offers and the public value it creates through enhanced services, outcomes and public trust. It has been demonstrated that the PRA is now well placed to meet all future challenges and opportunities to enable collaborative sharing of its developing systems and repository of spatial data in a real time environment by citizens, the business community and Government agencies. In this way it will further enhance the public value of property registration and contribute in a very real way to networked governance and citizen-centric services as advocated by the OECD (2008) and endorsed by government policy to transform Irish public services (TPS, 2009).

References

- APOCC (2004) The All-Party Oireachtas Committee on the Constitution, Ninth Progress Report, Private Property, Dublin: Government Publications Office.

- Budget (2010) Financial Statement of the Minister for Finance, Mr. Brian Lenihan T.D., 9 December, 2009 available at: http://finance.gov.ie/budget2010

- CSO, 2006 Central Statistics Office (2006) Census Publication on Housing, Volume 6, available at http://www.cso.ie

- C & AG (2007) Comptroller and Auditor General, Special Report no. 58 on eGovernment, October 2007, available at: http://www.audgen.gov.ie/

- C & AG (2008) Comptroller and Auditor General, Annual Report 2008, Accounts of the Public Services 2008, available at: http://www.audgen.gov.ie/

- Dáil Debates (2005) Vol. 610, No. 6, Thursday 24th November 2005, Registration of Deeds and Title Bill, 2005: Second stage, p. 1856.

- DBG (1996) Delivering Better Government Second Report to Government of the Co-ordinating Group of Secretaries – A Programme of Change for the Irish Civil Service, Dublin: Government Publications Office.

- Fahey, T., Nolan, B. and Maitre, B. (2004) Housing, Poverty and Wealth in Ireland, Dublin: Combat Poverty Agency

- Ferriter, Diarmuid (2009), Morning Ireland, RTE podcast, broadcast 31 December 2009.

- Kennedy, A., Coughlan, J. P. and Kelleher, C. (2009) ‘Business Process Change in E-Government Projects: The Case of the Irish Land Registry’, International Journal of Electronic Government Research, Vol. 6, Issue 1 pp. 9-22

- LRC (2006) Law Reform Commission, eConveyancing: Modelling of the Irish Conveyancing System, Ireland LRC 79-2006.

- Manthorpe, J. (2007) ‘Land Registration – a health check’, Registering the World; the Dublin Conference, Dublin Castle 26-28 September 2007, Property Registration Authority, available at: http://www.prai.ie

- McCarthy (2009) Report of the special Group on Public Service Numbers and Expenditure Programmes, Dublin: Government Publications Office

- Mohammadi, H., Rajabifard, A. and Williamson, Ian P. (2010) ‘Development of an interoperable tool to facilitate spatial data integration in the context of SDI’, International Journal of Geographical Information Science, Vol. 24, No. 4 April 2010, pp. 487-505.National Economic and Social Council (2004) Housing in Ireland: Performance and Policy, Background Analysis-Paper no. 3 The demand for housing in Ireland available at: http://www.nesc.ie

- OECD (2008), Ireland Towards an Integrated Public Service, OECD Public Management Reviews.

- O’Sullivan, J. (2007) ‘eRegistration and eConveyancing in Ireland: the story so far.’, Registering the World; The Dublin Conference, Dublin Castle 26-28 September 2007, Property Registration Authority, available at: http://www.prai.ie

- Pollitt, C. and Bouckaert, G. (2004) Public Management Reform A Comparative Analysis, 2nd edn., Oxford University Press.

- Rajabifard, A., Feeney, M. and Williamson I.P. (2002) ‘Future Directions for SDI Development’, International Journal of applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, Vol. 4 Issue 1, pp. 11-22

- TPS (2008) Department of the Taoiseach, Transforming Public Services Report of the Task Force on the Public Service, available at: http://www.bettergov.ie/index.asp

- Treacy C. and O’Sullivan J. (2004) ‘Land Registration in Ireland – Current Position and Future Developments’, Modernising Irish Land and Conveyancing Law Conference, O’Reilly Hall, University College Dublin, 25 November 2004, available at: http://www.lawreform.ie

- Wylie, J. C. W. (1986) Irish Land Law, 2nd ed., London, Professional Books Limited.